What is the Anterior Cruciate Ligament?

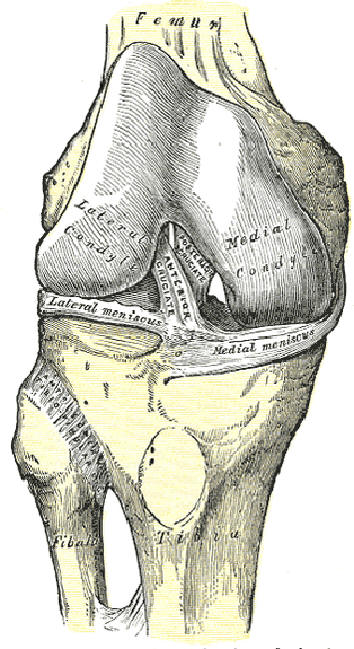

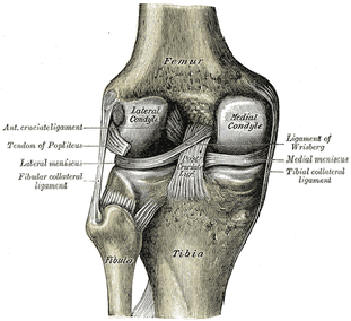

The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (or ACL) is one of the four major ligaments of the knee. It connects from a posterio-lateral (back & outside) part of the femur to an anterio-medial (front & inside) part of the tibia.

Damage to the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Damage to the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) frequently occurs with lateral blows to the knee (as happens with a tackle from the side in American football and often is accompanied by injuries to the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the medial meniscus, which is attached to the MCL; physicians are taught "… knee injuries come in threes - anterior cruciate, medial collateral, medial meniscus." Clinical studies, however, have noted a lateral meniscal tear to occur more commonly than the classic "terrible triad" noted previously. A damaged ACL can be confirmed (clinically) by a physician with the anterior drawer test, the Lachman test, or an MRI

Non-contact tears or ruptures of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) often occur when athletes moving quickly in one direction make a sharp or sudden change in direction (cutting).

In jump sports, anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) failure has been linked to heavy or stiff landing as well as twisting or turning the knee while landing. Studies indicate that women in jumping and cutting sports such as basketball, volleyball cheerleading, or football (soccer), are significantly more prone to anterior cruciate ligament ACL injuries than men; this is generally believed to be due to differences between the sexes in the angle between the hip and knee called the "Q-angle", general muscular strength, size of the trochlear notch, reaction time of muscle contraction, and possibly training techniques (a new study suggests hormone-induced changes in muscle tension associated with menstrual cycles may be an important factor). Women athletes are being taught safer jumping and landing techniques to better protect them from cruciate injury.

An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury can often be debilitating for far longer than a broken leg.

A partially torn anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) will usually be allowed to heal itself. A completely torn ACL will not grow back, probably because the lack of blood supply near the ACL. It must be replaced or left unattached. The ACL primarily serves to stabilize the knee in an extended position and when surrounding muscles are relaxed, so if the muscles are strong many people can function without it. However, lack of an ACL generally increases the risk of other knee injuries such as torn meniscus, and sports with cutting and twisting motions are not recommended.

Three Options for Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

There are three options for surgical anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) repair (see ACL reconstruction). In the first, two pieces of hamstring tendon are harvested from the back of the injured knee along with a small, attached chip of bone. These are woven together to form a single piece of connective tissue with pieces of bone at each end. In the second, the middle third of the patellar tendon is harvested from the patella (knee cap) to the tibia (shin). In the third, the patellar tendon is harvested from a cadaver. A fourth option, albeit not commonly performed by most surgeons, is to harvest the bone-patellar tendon-bone graft from the other (normal) knee. This option is typically reserved for revision operations and for some high-performance athletes requiring a faster return to play.

In all cases the new ligament is threaded through the knee arthroscopically and stapled or screwed into place at each end. Because bone grows much faster than ligaments, the ends of the new anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) becomes attached to the knee in just a few weeks. In about six months, the knee is very close to full strength and after a year or two the knee is generally stronger than before the injury.

Each method has its own pros and cons. Hamstring grafts are not as strong initially, since two tendons are woven together, but there is not significant clinical evidence that hamstring grafts fail more frequently than others. Patellar grafts are often cited as being stronger, but the site of the harvest is often extremely painful for weeks after surgery and some patients develop chronic patellar tendonitis. Replacement via a posthumous donor involves a slightly higher risk of infection. The risk is estimated to be 1 in 3 million. Additionally, donor grafts eliminate tendon harvesting which, due to improved arthroscopic methods, is responsible for most post-operative pain.

Rehabilitation for the Repair of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament

After surgery, the knee joint loses flexibility, and the muscles around the knee tend to atrophy. All treatment options require extensive physical therapy to build up muscle strength around the knee and restore range of motion. For many active patients, the lengthy rehabilitation period is more difficult to deal with than the actual surgery. External bracing is recommended for athletes in contact and collision sports for a period of time after reconstruction. Whether the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deficient knee is reconstructed or not, the patient is susceptible to early onset of chronic degenerative joint disease